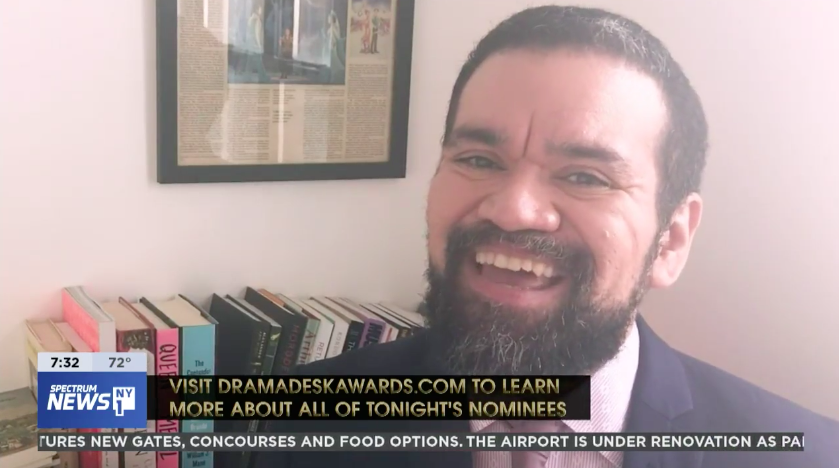

The day before the Mayor shut down theaters in New York City, I found myself sitting at a matinee performance of Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice. As much as I enjoyed Duncan Sheik’s music and getting to see Suzanne Vega perform live, I was grinning from ear to ear because it was the first time I’d seen Joél Pérez as a leading man. Playing the suave Bob, who thinks of himself as a modern man ready to embrace an open relationship with his wife Carol (Jennifer Damiano), Pérez brought indelible charm, surprising vulnerability, and sang Sheik’s score like Andy Williams at his peak doing Burt Bacharach on a TV show, all while sporting a killer mustache. Bravo, Joél.

It was remarkable to see a Latinx actor bringing to life a character played in the 1969 movie by Robert Culp, the white actor who went on to play FBI Agent Bill Maxwell on The Greatest American Hero. As Pérez sent me back into what quickly would turn into a live-theatre-less nightmare of a world, I kept thinking how he is my idea of what an American hero should be: extremely talented and always willing to show us new sides of his craft.

When Pregones/PRTT announced their Remojo series, in which they highlight works in progress, would be streamed on their website and other channels, I was thrilled to discover a new side of Pérez: he’s also a writer. I quickly read the excerpt he sent me of Colonial, which will be shown on July 20th, in which he sets up an enchanting tale of a young man who inherits a house in Puerto Rico, leading him into an examination of self, and identity. I spoke to the multi-hyphenate Pérez about writing, being a Latinx stage actor, and why comedy might be the most efficient way to show the truth.

Before seeing that you were doing Remojo at Pregones/PRTT I don’t think I even knew you were a writer. How did you end up wanting to write Colonial?

Well, you know, I’m Puerto Rican and Puerto Rico has such a complicated, messy history with the United States and it’s not something people really talk about. Even my parents, my dad moved to Massachusetts when he was 12. And then my mom moved to Boston when she was like 22 after she graduated college. So they’ve never had a boricua kind of attitude. We have family in Puerto Rico, but they’re not super politically active. And then moving to New York, my very first acting job actually was at Pregones, and it was interesting to meet all these theater Puerto Ricans. I was like, this is a thing? I guess so, cool. I didn’t know there were other people like me. Expats who were politically active too.

When I started to actually research the history of Puerto Rico, and its treatment of that kind of colonial mentality that still exists on the island, I found it really interesting. I just read this really great book called War Against all Puerto Ricans, that tracks the history of the colonization of Puerto Rico. And that’s really where the the nugget of the idea started. I did the national tour of In The Heights and we did a stop in Puerto Rico. I remember acting there and performing and I had this dream of someday I’m gonna move back here, and have a chapter of my life here. So that kind of led me on this thought exercise: if I were to be a young person and moving to Puerto Rico and trying to reconnect with my culture, what is that? What does that mean?

Then I learned about the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, and how these mythic figures like Pedro Albizu Campos, which had a lot of parallels with the Black Panther movement in the United States and fighting for independence of the island. It’s interesting now thinking about how the Black Lives Matter movement is really mobilizing even more in the States and how linked I feel that is with the colonization of Puerto Rico. It feels like it’s just a really an important story to tell. A lot of people think Puerto Rico is just a vacation spot where cruise ships stop and hang out, but the actual citizens of the island are really treated as second class citizens.

I’m a sucker for alliteration and in the first page of the script you write “spicy servant stepchild,” about Puerto Rico, which was heartbreaking and hilarious. The script is tender and lovely and human, but also very funny. How much of your training at the Upright Citizens Brigade influenced your sense of humor?

I love comedy, it’s a really powerful tool to get people’s defenses down to really cut into deep feelings. I think of people like Stephen Adly Guirgis and his writing is like, you’re laughing one second and then crying the next. So that’s usually kind of how I approach a lot of my writing: try to start from a place of humor to let people’s defenses down. Because it’s already a pretty heavy subject, I don’t necessarily want to add more shit on top of it. I’d rather try to find a way to make it feel accessible and entertaining. A big thing at UCB is their approach to comedy is truth and honesty. The audience laughs at something because they think, “wow, that’s so true.” So it’s not really about being like a big crazy character or being super witty or crazy, it’s just like being really honest.

The Wednesday before New York City shut down theaters, I actually went to see Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, which I really enjoyed. I wish that had been my last show instead of the depressing The Girl from the North Country, but that’s another story. What have you been up to during quarantine? How long did it take you to go from uncertainty into, “I might as well create something” mode?

I’m the kind of person who always has a bunch of stokes in the fire, I’m always working on 30 different things. So, in many ways, there was a period of despair in terms of I can’t believe I can’t do anything and I’m really being forced to just slow down and be with my thoughts. I had really exciting projects that I was supposed to do. I was going to do As You Like It again this summer for Shakespeare in the Park, I was really sad about that. I had a really small part in the Tick, Tick…Boom! film that was supposed to be shooting this summer.

As an actor, it’s all about momentum. Working is like an avalanche, the next work begets work and the next job your next job. And so when you’re forced to just stop, that’s really scary because that’s our livelihood. I don’t have a backup plan, I don’t have another source of income, I don’t have a desk job that I’m doing on the side. So it took a while to be strategic about what you want to do next. But then it also gave me the time and energy to work on some writing projects that had been percolating for a little while.

This opportunity to write Colonial was something that I had talked about to [Pregones/PRTT Co-Founder and Artistic Director] Rosalba Rolón about a while back. She told me about Remojo which would be online and something I could work on from home. This was such a great opportunity to finally sit down and start working on that thing that’s been kind of marinating in my brain for a while.

There’s also this movement on the side with, We See You White American Theatre and it’s bringing to light a lot of the issues that exist in our industry. We’re all kind of being able to sit and think about how we have been treated. I think a lot about my own career as an actor and ways that I’ve felt both tokenized, but then also given opportunities that other people haven’t gotten and people that have opened doors for me. I always try to keep that door open for the next generation of people.

As an actor, it’s all about momentum. Working is like an avalanche, the next work begets work, and the next job your next job. And so when you’re forced to just stop, that’s really scary because that’s our livelihood.

joél pérez

I don’t mind being alone, but sitting alone with your thoughts for over 100 days is too much.

In the past I’ve always been like, I’m such an introvert. But who the fuck am I kidding?

I don’t miss hanging out with people necessarily but I miss dealing with their problems instead of dealing with my problems. Have you in all this time picked up maybe a new skill or have you learned something about your own craft that you want to continue exploring if the world ever goes back to live performances in community?

I’ve been forced to really look at the tools that are at our disposal. I feel like theatre is such a collaborative art form. As an actor, you’re just like one little piece of the puzzle. And so, I’ve been thinking about new ways to be creative and tell stories. I’ve got camera, I’ve got a green screen, I’ve got some lighting equipment. Why not think about new ways of telling stories and not necessarily feel like we need to follow the systems that are in place?

And I think a lot of that about in thinking about Broadway, why is the goal or the dream that we’ve all been told that Broadway is the thing, and then we stop and think, is that really the thing? Why do I think that that’s the thing and actually when I stop and think about it, what are the opportunities that are presented?

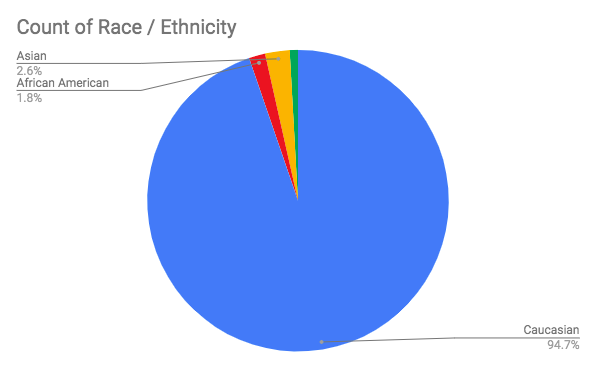

Last year I was doing Kiss My Aztec, for example, in California, and that was cast by Tara Rubin casting, but I didn’t get cast with her—I had been doing readings of the show for a while. She saw the opening, and she was like, “Joél, I had no idea that you were so funny.” In my head I was like, “Yes, I am!” But to her credit there is nobody writing musical theatre comedies for Latinos. That doesn’t exist. It’s not even like I’ve had the opportunity to audition for those roles, because nobody’s writing them. It doesn’t exist in what’s being offered for Broadway or regional theater audiences. There isn’t even the opportunity for Latinx actors to be funny. We’re always in torture porn or it’s some kind of bad story that we have to tell.

After she said that to me I thought: maybe there’s a new there’s other ways to get the kind of career that I want. Quarantine is a time to really think about what’s the access, what are the opportunities? What are we investing in? I’m so grateful that the very first job I ever had in New York was at Pregones/PRTT, so why not try to uplift theaters and groups that are already trying to give voice to these groups, rather than feeling like I’m begging for scraps from these other institutions that just see us as diversity quotas?

It’s very funny to me, in a very twisted way, that we are aware that Off-Broadway and Off-Off-Broadway is where the experimental, fun, and interesting things are happening. And yet we all talk about Broadway constantly. I think about Broadway almost as the current president. If we just had ignored him from the beginning and not given him so much power, we would be living in another world. There’s something that I’m also very interested in, you said, for instance, that no one’s writing musical comedies for Latinx people. And this brings me to the burden of representation. People who aren’t white are often asked to open doors for others, and many of us live in fear that if we get something wrong, no one’s going to hire anyone who looks like us again. White people get to only think about their individual careers, meanwhile I’m like: if I fuck up, Latinos are being cancelled.

Totally.

With that in mind: why do you want to make theatre? And do you ever feel that fear about messing up and hurting other POC because institutions see us all as the same?

Yeah. So, I grew up super religious. My father’s a Pentecostal minister. I grew up very fundamentalist Christian, and so there is something that I find very similar to the experience of going to church that I get from going to the theater. It’s like the same ceremony. The stage is the altar, the play is the sermon and the audience is the congregation, and we’re learning about human experience and, I feel, a kind of connection to this divine storytelling.

It’s a feeling for me that I think has evolved over time. I think the older that I’ve gotten and been in this industry, it’s kind of distilled into how that’s a very powerful tool for storytelling and for social change. A younger version of me was more interested in the fun entertainment side of it, and I think the older I’ve gotten, I am more interested in telling stories of underrepresented people and bringing to light experiences that people don’t know that much about.

Theatre can be like a teaching moment or a way to see the world differently. And there’s something so special about being in a live audience, surrounded by people, breathing together and seeing a thing together. Every performance is different, and every show is a little different. I think that’s why I love it, why I keep coming back to it.

Theatre is such an actor’s medium. It’s really on us to be the ones to tell the story. Sure the director directs it, and there’s lighting and there’s sets, but the people who show up every day to tell the story are the actors on stage, and the stage managers backstage, and we’re the ones who are telling that new story every day.

And then in terms of, if I represent all Latinos, I don’t know. I try to just do the best that I can do and I hope that it sets the precedent for better representation. But that’s not always the case. I think a lot about when I did Fun Home, for example [Off-Broadway at the Public Theater and then on Broadway], I met Jeanine Tesori and Lisa Kron at the Sundance Theatre Lab, they thought, “You should be in our musical.” So when they did a reading, I got asked to be a part of it. My Latinidad wasn’t part of that story, though.

Yes, I existed on stage and that is cool, but you know, Roy, was based on a white man. There was nothing about that character or that story that pointed to my Puerto Rican-ness or Latinx identity, which in some ways, that’s really great. But I would have liked if that meant that then all my understudies were Latino, which wasn’t the case, every understudy was a white guy. It’s not like that set a precedent to be like: when we think about this track, let’s think about it as a non-white person, let’s have a person of color in this role.

There was just white guy, after white guy, after white guy, as the people that were brought in to replace me, or to be understudies, or vacation swings, and stuff. At the time I didn’t really think much of it. I thought it wasn’t really my place because I wasn’t on the creative team. But I always kind of clocked that. Same with Roberta Colindrez, we had a joke where we called each other the Browns, that was our fake last name. It was so weird that the two of us felt we kind of like snuck into this room, but all our covers were white people.

So it always felt a bit like we were an exception to the rule instead of setting a precedent for what this role could be going forward. At the end of the day, Broadway is a business. When I did Oedipus El Rey, this super cool Chicano take on Oedipus by Luis Alfaro, which Chay Yew directed [at the Public Theater], I also got cast in a lab of Moulin Rouge! The Musical. I played this character named Santiago, who in the movie was the Narcoleptic Argentinian. I don’t know if you’ve seen Moulin Rouge!

I have. Love the movie but didn’t like the musical.

That part is just so shitty. I guess he has like a little more to say now, but when I was doing the reading there was like nothing to do. He was just a hot-headed Latino, just a one-dimensional character. They weren’t doing the movie, they were doing the musical, the trope of the hot-headed Latino has been done a bajillion times.

If you’re interested, you could perhaps do something different, and I got the vibe that they were not into that, or that they were a little flabbergasted because I think for them, it’s like: you’re a Latino in a big Broadway musical. That should be enough. The existence of this character should be enough. I had to kind of reconcile these feelings of, I should be so happy doing this big fucking musical, I should be on cloud nine.

But actually, I was really happy at the Shiva Theater doing this tiny little Oedipus El Rey. But Moulin Rouge! paid more than being at the Public. We’re often forced to make financial choices or compromise our feelings or stance on stuff because of money. We all need to make a living and you think it’s worth my soul dying a little bit because this project will pay a lot.

We’re often forced to make financial choices or compromise our feelings or stance on stuff because of money.

joél pérez

Can we talk about this homecoming of sorts of yours to Pregones/PRTT? What does it mean to be back and to see the company do such remarkable work when it comes to access?

I’ve always been a part of the Pregones/PRTT family since I started here. I always pop in and we’ll do a little reading. I love going to see their shows. It’s the only place in New York where I feel like my culture and my art mix. Quarantine has been a time to really think about where I want to focus my time and energy. I think a lot about how Pregones/PRTT has this gorgeous theater in the Bronx, they have this gorgeous theater right in midtown on 47th Street, right in the middle of everything. They have these beautiful spaces that can present really interesting art, and so then I think about: why am I focusing on really trying to get to be in a Manhattan Theatre Club play literally around the corner from the Puerto Rican Traveling Theatre?

Why can’t I do a show at the Puerto Rican Traveling Theatre that actually, I care so much more about? I feel like we often have blinders on as to like: performing in these big, cultural institutions means success. But then that also means Pregones struggles all the time to get press to come to see their shows. You wrote a really wonderful article about last year, right?

I reviewed ¡Guaracha! for the New York Times. The way I see it is, if I do work for predominantly white institutions, I might as well cover the works of my people.

Yeah, and people don’t go to these theaters because they don’t know about them or they’re seen as, I don’t know, cultural experiences as opposed to a really good play—put in this box of like, I’m gonna go see a Museum of Natural History experience about Puerto Ricans rather than, I’m just going to go to the theater and to sit and see a play. I also think it’s one thing to sit back and complain about it and another to do something about it. Let’s try to contribute to the cultural landscape and feel like our voices can be heard and that our stories matter, because they do.

I don’t know how often you get to talk to a journalist who’s not white…

Never.

…as a learning process, although this is obviously not your work to do for me, as I try to decolonize my own mind from the type of white journalism I read and grew up with. But in the spirit of trying to collaborate and show the world how we can un-learn things, what is something about your craft you’ve always wanted to talk about, but that journalists, including me now, haven’t even asked about?

I’m finding myself in a in a weird place. I’m thinking a lot about how a lot of people of color go through these training programs and go through musical theatre training programs. I have my book where I learned my Hammerstein and I learned my Sondheim and I learned all my classic musicals—I have this legit musical theater training. And when you actually get into the field, you’re then forced to do hip-hop musicals, or “urban music,” because that’s the roles that are being written for people of color.

Those are the roles that are being produced for people of color. And so you have this whole generation of incredibly trained people of color who never get to flex those muscles because we’re not part of that narrative. Or we are like a concept—it’s a black Oklahoma! or a Latino version of XYZ.

This doesn’t really answer your question about craft stuff…

I do feel a burden sometimes that when those opportunities are presented to me, I want to do a really good job, so that hopefully, when an opportunity comes up for another Latino actor, they are taken seriously and they’re not tokenized. I want them to feel like they have an opportunity because hopefully, I showed a producer, director, or writer that I have craft and the training to back it up.

But then that brings me back to why am I even trying to work with people I need to prove so much to? Lisa Kron said something about women versus men that I think also applies to people of color and white people: Men get jobs based on potential, women get jobs based on their accomplishments. White people sometimes get opportunities based on potential, people of color get those opportunities only after they’ve proven themselves. It feels like they’re not opening doors especially for young people. This still doesn’t answer your question about craft though…

Maybe we can come back to that in the future.

I guess what I’d say about craft is keep yourself really as a multi-hyphenate. It’s really important to have people who can write, direct, act, produce and create in an all-encompassing way. That’s how we’ll be able to lift each other up and create work outside the system we have.

For more on Joél Pérez visit his official site. For more on Remojo, visit Pregones/PRTT.